As If One Giant Black Hole Weren’t Enough, What’s a Galaxy Doing with Three?

Last Thursday, my colleague John Matson described a truly amazing galaxy known, somewhat unromantically, as BX442. It has a majestic spiral pattern while hundreds of its galactic contemporaries were gawky and misshapen—a peculiar and special anomaly which suggests to many astronomers that cosmic pinwheels are ephemeral art forms, like Tibetan sand mandalas. John's piece spurs me to talk about an equally dramatic image from nearly the same epoch of history.

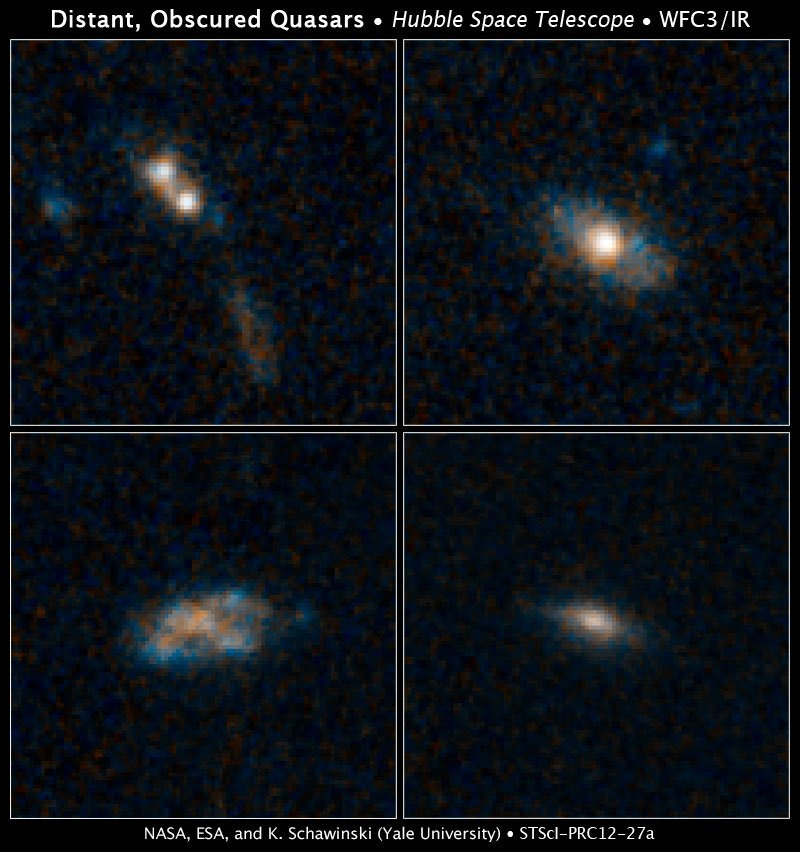

It shows a galaxy riddled with great big clumps of gas, at least three of which (labeled A, B, and D) are so strongly ionized that they must contain giant black holes, with a mass of 3 to 20 million solar masses. Such a triplet is rare, and what makes it even more remarkable is that there are no debris trails or other signs that the galaxy is the product of the collision of several galaxies. Evidently all three holes are homegrown—the first known example of multiple giant black holes forming in the same galaxy. Kevin Schawinski and his colleagues published this Hubble Space Telescope image last fall, and he told me about it at the American Astronomical Society meeting in January.

Usually when astronomers marvel at supermassive black holes, they focus on holes that date to the first billion years of cosmic history. Those ancient holes managed to reach their enormous proportions in not a lot of time. The rapidity of their growth, astronomer Jenny Greene argued in our January issue, means they probably formed by the direct collapse of immense gas clouds. To have assembled the holes in the usual multistep process—stars are born, stars die, dead stars collapse to black holes, black holes agglomerate—would likely have taken too long.

But the discovery by Schawinski's team poses the opposite problem. The galaxy lies at a cosmic redshift of 1.35, corresponding to a cosmic age of 4.5 billion years—more than enough time for a black hole to grow big. If anything, it was too much time. The era of supermassive black hole formation should have long since been over. Moreover, the holes, being heavy, should all have sank to the middle of the galaxy and fused into one. Thus the triplet indicates black holes were continuing to form. That multistep process might operate after all.

The gaseous clumps that host the holes, inelegant though they may appear, are themselves fascinating. Our own galaxy has giant interstellar gas clouds, but these clumps are a different order of giant. Spanning thousands of light-years and containing up to a billion solar masses, they are to our galaxy's clouds what Jupiter is to Earth. Astronomers began noticing them in the mid-'90s as the Hubble, Keck, and other telescopes started to make photo albums of galaxies at redshifts beyond 1. People's initial instinct was to see clumpy galaxies as the aftermath of galactic collisions, but they turned out to be galaxies whose interstellar gas had curdled.

Galaxies back then contained proportionately much more gas—10 to 50 percent by mass, versus a few percent for today's Milky Way—and the gas was roiled by vast rivers flowing in from intergalactic space (like the flow in the artist's conception at right). Instead of passively riding on the gravity of other matter, gas actively reshaped the galaxy. It fragmented under its own sheer weight and strong turbulent motions, taking stars along for the ride, and most clumps went on to create mega black holes.

Clumpy galaxies have about the same mass, size, and numbers as the Milky Way. They have generally flattened disk shapes and, as BX442 shows, all the prerequisites for spiral patterns. So they appear to represent the turbulent adolescent phase of systems like our galaxy. "All this suggests that they are the typical progenitors of Milky Way-like spiral galaxies," says astronomer Frédéric Bournaud.

To hear astronomers play down the importance of major galactic collisions is to hear the creak of a pendulum swinging back. When I started my career in science-writing nearly 20 years ago, astronomers had taken to collisions with the zeal of new converts. And indeed they have confirmed the importance of massive pileups to the creation of the very largest galaxies. But they now think that most galaxy evolution, star formation, and supermassive black hole growth are driven by internal processes and the occasional tickling from a minor close galactic encounter, like the putative mini-galaxy that may have set in motion the spiral pattern in BX442. For instance, the galaxies in the image at left all have actively feeding supermassive holes, but only the one at the top left is undergoing a major collision (and it is the sole example in a sample of 28). The beauty of galaxies needs no kick from the outside. It comes from within.

Credits: NASA, ESA, Kevin Schawinski (first and third images); ESA–AOES Medialab (cold flow artist's conception)